Of the various aspects that make up the teaching of the English language, the least attended to is that of pronunciation and the result of this is that students who, although they constantly express themselves in that language in class and maintain frequent exchanges between them, when they travel to a country where that language is spoken experience great difficulty in understanding English speakers and even more so in making themselves understood by them. Teaching pronunciation has been called “the Cinderella of English teaching” for a reason.

We think that the problem stems from the false assumption that English and Spanish use the same alphabet, the Latin one. It is true that it is composed of graphs that represent phonemes, this is, signs that mean sounds. And that is precisely where the problem lies, since alphabetic writing does not always, and this is particularly the case in English, guarantee a one-to-one correspondence between phonemes and graphemes. In Spanish, with some few exceptions, the symbols correspond to the same sounds, without counting, of course, the allophonic differences (of which we are not even aware). But the phonetic evolutions of a language are created at a different rate from the written evolution. Thus, in English several different combinations of letters can produce the same sound. And the same spelling (such as the vowel a) can be pronounced in up to seven different ways within a word, with the consequent semantic variation.

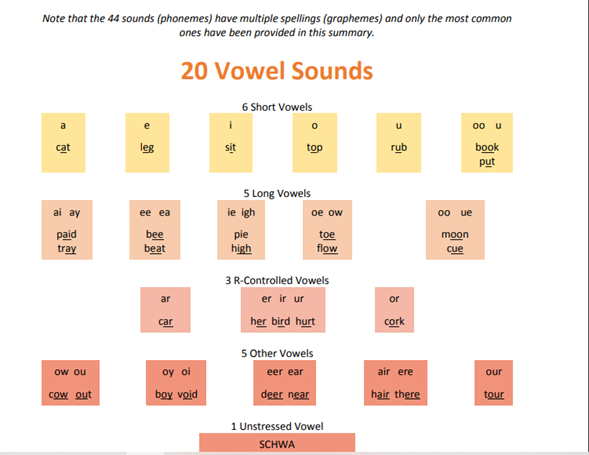

The surprising thing is that we never teach our students the alphabet in English because we assume that it is the same as Spanish with the only difference that the latter has one more letter, the ñ. (Before, Spanish included the digraphs ch, ll, rr, but the Royal Academy of the Spanish Language eliminated them from the alphabet. But we forget the small detail that in terms of phonemes, Spanish has 27 and English around 44. And we say “around” because there is not even a consensus of how many vowels and consonants there are in English. Depending on the speaker and the dialect, there are variants only recognized and practiced in certain regions.

In addition to this, our teaching is still much more visual than auditory. We base it on the blackboard, projections (often soundless), use of books and notebooks. When the teacher introduces a new word, the first thing he does is write it on the board so that the students assimilate it. That is why they absorb its graphic rather than phonetic form. It is in this way that they can pronounce it, adapting it to the sounds they know, since they do not identify those they do not know.

With the introduction of the Communicative System half a century ago, it was sought to reinforce communicative competences before linguistic ones; it would have been thought that greater importance would be given to listening comprehension and pronunciation, vital elements of oral comprehension, but this has not been the case.

There are two ways to study and practice pronunciation: intuitive and analytical. The first is based on the imitation of the teacher’s pronunciation, something not very effective if the teacher had the same shortcomings during his own learning. Aware of this, teachers are not very willing to insist on pronunciation. The second is the analytical, which is reinforced by explanations of the articulatory processes.

Charles Fries, the linguist who created the Aural-oral method, noted: In learning a foreign language, then, the chief problem is not […] learning the vocabulary items. It is, first, the mastery of the sound system…(1) That is, the opposite of what we do. The Aural-oral method would be much more compatible with the Communicative Approach. Fries warns that the student must first develop the auditory capacity to perceive the new sounds, before attempting their production. Since we do not do this, our students generally speak English with the sounds of Spanish. The only ones that are saved are the students of bilingual schools, where students learn the language predominantly by listening.

Most authors of texts have treated the subject of pronunciation marginally. In 1992 Scott Thornbury criticized this apparent lack of interest: “Developments in the teaching of pronunciation do not seem to have kept pace either with developments in the teaching of language generally, nor with recent insights into speech production.”(2) He also pointed out that current materials and teaching aids reflect that the present approach to pronunciation teaching is segmental and therefore in conflict with suprasegmental phonetics.

Adrian Underhill, very dedicated to Pronunciation teaching, wrote Sound Foundations, which is very recommended reading for all English teachers. In it he suggests creative

ways to deal with pronunciation training. On the other hand, Steve Hirschhorn noted that “Celce-Murcia, Brinton and Goodwin, in Teaching Pronunciation, 1996, offer us a vision into the future with a variety of well-documented activities and ideas for the

teacher to try.”(3)

The International Phonetic Alphabet is a very important tool to teach pronunciation. Yet, it is surprising that every English classroom does not have one in permanent display and use. We are not suggesting that teachers should make their students learn it by heart all at once, but it is a tool that all language educators should employ often.

Other phonological aspects in the suprasegmental level that intervene in the communicative process, such as rhythm, pitch, intonation and stress are of utmost importance and they were referred to by professor María de la Lama in a previous article.

___________________

(1)Fries, C.

(2)Hirschhorn, S.

(3) Thornbury, S.

References:

Fries, C.C. Teaching and Learning English as a Foreign Language 1945 Ann Arbor: Uni. of Michigan Press

Hirschhorn, S.2004. The recent history of pronunciation teaching in English language teaching. https://eflmagazine.com/the-recent-history-of-pronunciation-teaching-in-english-language-teaching-adapted-from-a-2004-lecture/ Retrieved April 27, 2022.

Thornbury, S. 1993. Having a good jaw: voice-setting phonology. ELT Journal, 47/2, 126-31.