Some pedagogical practices considered traditional or mistaken tend to keep alive in spite of advances and new knowledge.

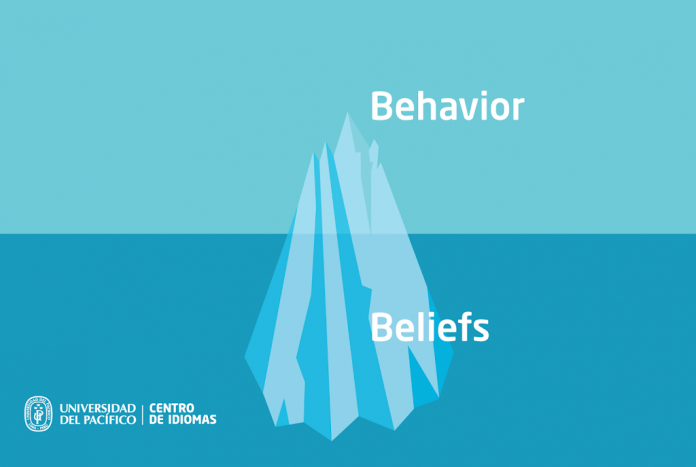

Many factors could be identified to explain this situation. Among them, we could mention teachers’ conceptions and beliefs regarding the teaching-learning process, conceptions and beliefs that teachers already have, based on their own experiences (Pozo et al., 2006), and that will guide teachers in the definition of the activities they will apply in their classes, whether they are planned or not.

Beliefs, true or false ones have an affective, evaluative and episodic nature that would be working as a filter, through which all new phenomena are interpreted, even when knowledge and beliefs are interrelated (Pajares, 1992).

Beliefs are built at an early age and tend to perpetuate even when reasoning, time, school or experience produce conflict. Furthermore, Pajares (1992) pointed out that the older the belief is, the harder it is to change it; something that does not happen with recent beliefs, as they are more vulnerable to changes. This explains why adults rarely modify their beliefs; grownups tend to maintain them even if they are based on incomplete or incorrect knowledge. For this reason, teachers with many years in teaching show difficulty in changing schemes and in adapting themselves to new trends.

In addition, we could consider as another factor the professional preparation that teachers may have received. In this professionalization period, teachers may have acquired or instituted certain knowledge that could steer or influence their pedagogical practices. Early experiences and prior knowledge strongly rooted in teachers could cause interference in the acquisition of new perspectives and knowledge of the process of teaching and learning. For this reason, although teachers may hold higher college studies or may have received refresher training on new knowledge, it is not reflected in their performance in the classroom and, on the contrary, they continue applying a traditional teaching method.

In any case, we still meet misbeliefs such as the ones that are practised with the precept that their extensive or exclusive use will guarantee students’ success in learning a language. We still find cases in which the emphasis on these practices is such that considering paying more attention to other sources of knowledge is forgotten even if doing so will entail a more comprehensive approach for teaching.

Some of these misbeliefs are closely related to concentrating on providing a number of grammatical rules or long lists of vocabulary as well as offering a bunch of materials such as books, copies of exercises, links and so on. Another common one is that in which the solely use of a platform is synonym of use of technology in its most advanced version. In this new series we are launching, our team of researchers will share some insights about these misbeliefs.

Do you know any other beliefs that bound our teaching in a certain way?

What could we do in those cases?

**

Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ Beliefs and Educational Research: Cleaning up a Messy Construct. Review of Educational Research, Vol. 62, No. 3, pp. 307-332.

Pozo, J., Sheur, N., Pérez, M., Mateos, M., Martin, E., De la Cruz, M., (2006) Nuevas formas de pensar la enseñanza y el aprendizaje. Las concepciones de profesores y alumnos. España, Grao.

*Los mensajes y/o comentarios de publicidad u otra índole, no relacionados con el artículo, serán eliminados y reportados como SPAM*

Estimated reading time: 2 minutes, 47 seconds